Does the circular economy support sustainability? Or are we chasing false solutions? This two-part series begins by unpacking the root causes of the ‘wicked problems’ causing our sustainability crises, and then calls out some of the false solutions emerging from businesses around the world.

8 minute read

Back in 2020, the UNSSC invited me to support its excellent (and free) 5-week circular economy course. I was asked to answer a complicated question: is the circular economy sustainable? I called-out examples of ‘circular-washing’ and double-standards. I also highlighted bold ‘ambitions from global businesses that might improve sustainability – but could just as easily rebound into even more consumption and waste.

The UNSSC team invited me back again this autumn. And yet now, despite seeing businesses with circular ambitions popping up everywhere, I’m even more concerned…

Stealing the future

I’ve immersed myself in the circular economy for over 10 years now. Over that time, I’ve researched and written about hundreds of circular start-ups. Mostly, they’re developing new materials, or finding value in closing the circularity gap in other supply chains – by reselling, repairing, renting, remanufacturing, or recycling.

But despite all those inspiring examples, and the increasing interest from big businesses, our enormous global challenges – climate change, ecosystem destruction, and social inequality – are not being resolved.

Instead, they’ve worsened, becoming crises – global emergencies – undermining our ability to survive and thrive. We stand accused of stealing the future from younger generations.

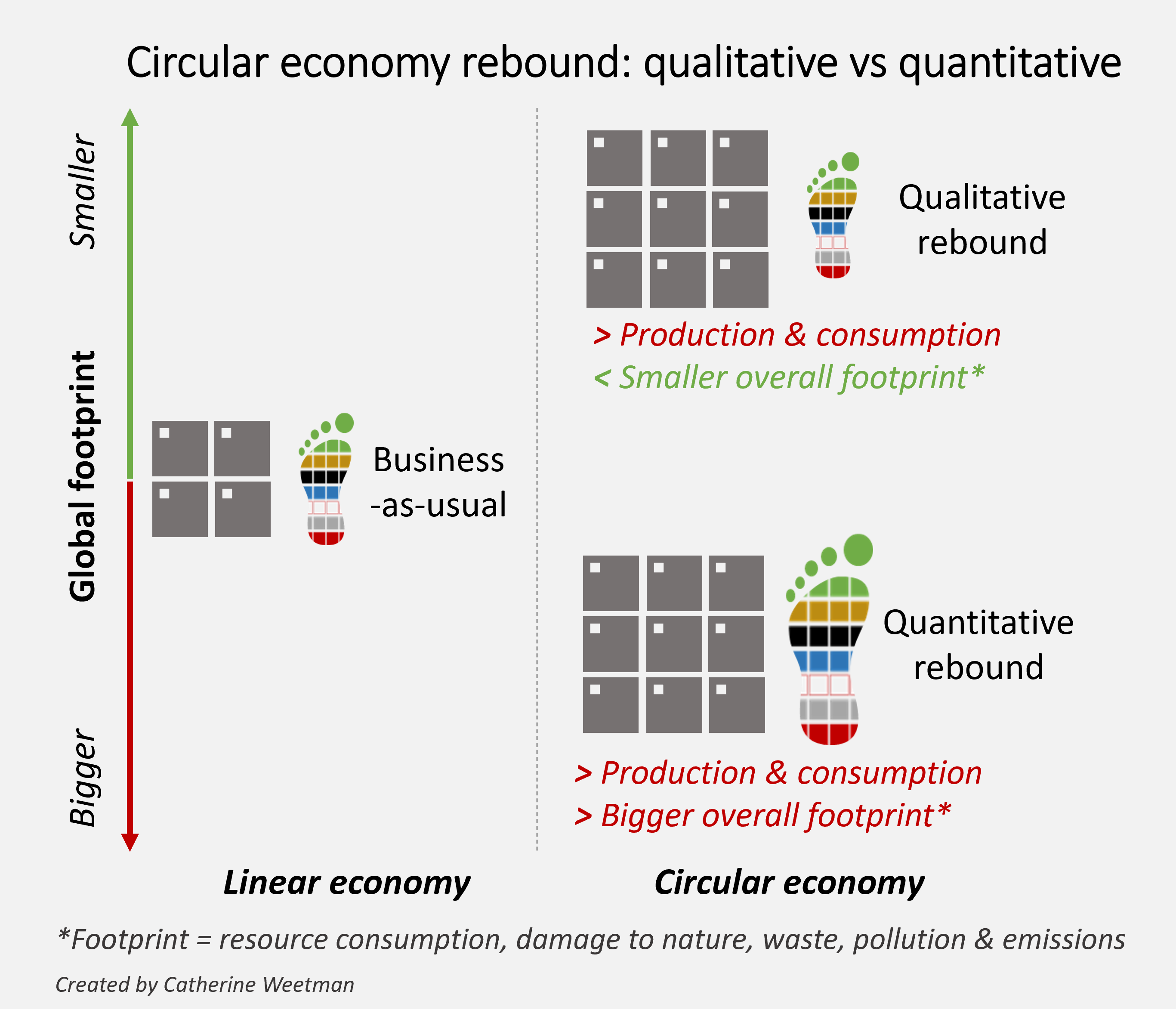

I think the circular economy is the best tool available to design new systems, that help conserve and regenerate materials, ecosystems, and communities. But it’s not straightforward. If we look closely, we can see circular approaches with unforeseen consequences. I think there are a number of ‘false solutions’ –ways of ‘going circular’ that don’t improve sustainability and may even cause negative impacts.

In this two-part article, I want to challenge a few potential pitfalls. I’m asking tough questions and challenging my own assumptions, aiming to avoid wilful blindness.

To explore the question of whether the circular economy supports sustainability, in Part 1, I’ll unpack the root causes of ‘wicked problems’ causing our sustainability crises. Next, I’ll spotlight some of the false solutions that could take us in the wrong direction.

In Part Two, I’ll raise the issues of ‘rebound’, then outline what we need to do to be truly sustainable: to live within the limits of our one planet. How can we slow down our production and consumption, so we shrink our footprint? And how do we do this without undermining our wellbeing – so we have enough, for all of us, forever?

Every day, we’re reminded about the immense scale of the problems we face. Now, though, it feels like we’ve reached a tipping point. We’re in a different world – we’re in the Anthropocene, where we’re having so much impact on the other living creatures on this planet, that we’re affecting the earth system itself.

“At their core, the problems we face today are no different from those our ancestors faced: how to find a balance between what humanity takes from Nature and what we leave behind for our descendants.

While our ancestors were incapable of affecting the Earth system as a whole, we are doing just that.”

The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review

It’s becoming clear that we’re destroying the very systems that we depend on – wrecking nature and the social systems that enable us to survive and thrive.

Wicked problems

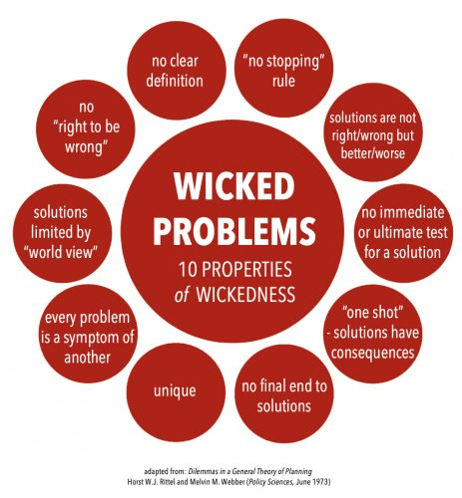

Our precarious situation is becoming all too clear. We’re facing enormous, inter-related, complex problems – “wicked problems”.

Gradually, we’re realising that our common challenges – climate chaos, the death of nature, more recently, the covid 19 pandemic, and the unfairness we see all around the world – can only be resolved with a new system.

Problems like these – complex, interconnected, global, multi-faceted – are classed as ‘wicked problems’. Wicked problems were defined back in 1973, and Christian Sarkar and Philip Kotler’s Wicked7 Project highlights 10 common characteristics of ‘wickedness’. It’s worth noting that the solutions to wicked problems are not right or wrong, but better or worse than we have now.

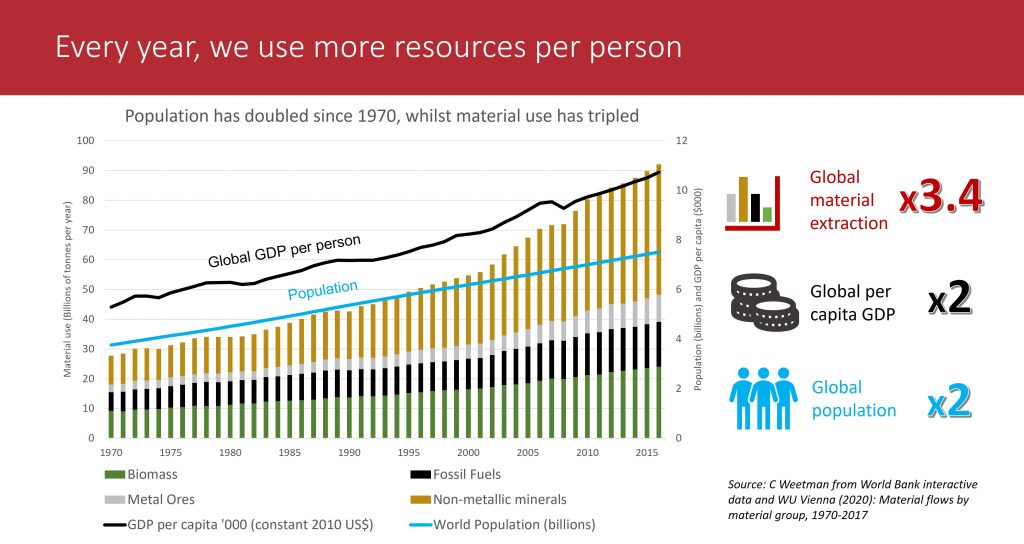

Every year, we’re using up more resources per person

After thousands of years of human progress, and nearly 300 years since the first Industrial Revolutions, in the last 50 years our population and GDP (Gross Domestic Product) per person have doubled.

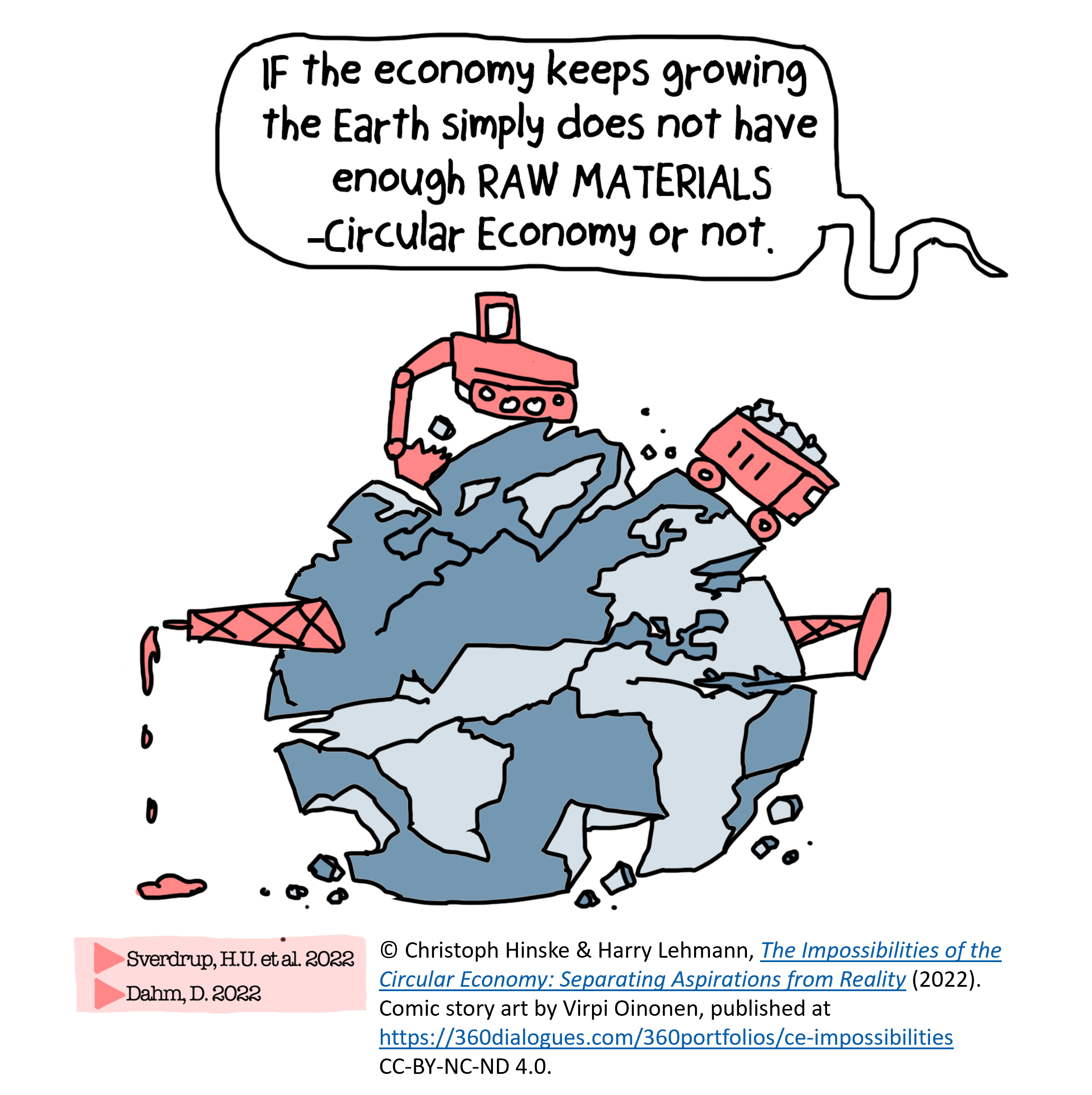

Yes, instead of getting more efficient, our use of materials has risen even faster, increasing by a factor of 3.4 over the same period. In other words, resource consumption has grown 70% faster than world population.

We now use around 100 billion tons of materials, every year – a sustainable level is less than half that.

Our thirst for materials (for both toys and tools) is fuelling the climate emergency, destroying nature, and undermining human health.

And yet, most resource extraction and farming systems aren’t helping all of us around the world: wealth, progress and opportunities are becoming less fair, and less equal. Higher-income societies, driven by big businesses, are consuming far more than their fair share of resources: destroying our common future.

The United Nations Global Resources Outlook 2019 highlights the disparity – with high-income countries consuming 13 times more than low-income countries, and five times more than lower-middle income countries.

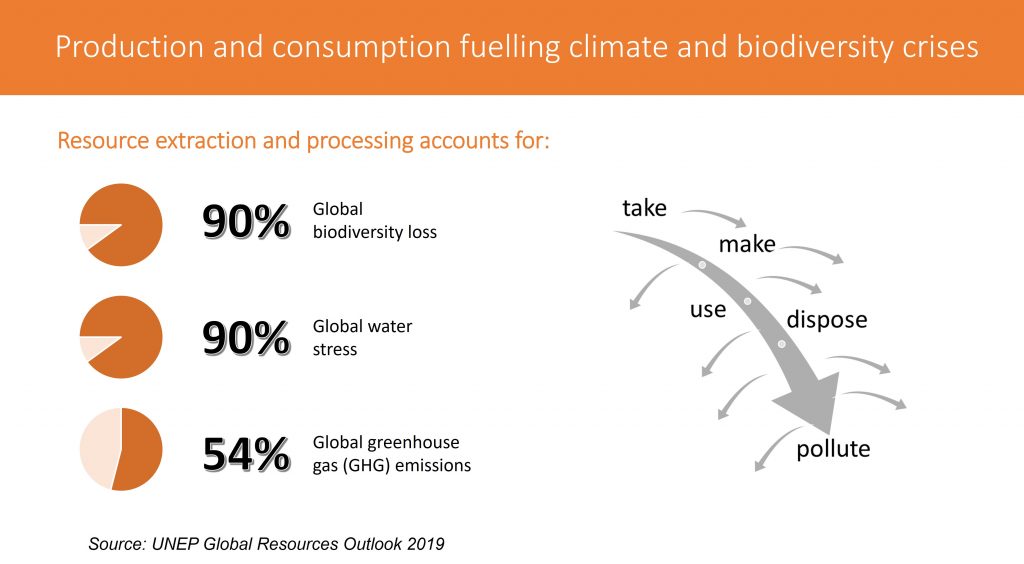

Take, make, waste and pollute

The United Nations Global Resources Outlook tells us that resource extraction and processing causes nearly all global biodiversity loss, almost all global water stress, and over half of global greenhouse gas emissions. In other words, to get to grips with the climate, water and biodiversity emergencies, we must focus on big reductions to our material footprints.

The average person will use over 30% more resources by 2060

Despite this, predictions show that extraction levels will continue their exponential upward trend. On current trends, our material use will more than double by 2060.

It’s clear that we’re using up more materials to make more products that we buy, use, and then discard. What’s more, we replace things more frequently – it feels like every sector is borrowing ‘fast fashion’ tactics. We’ve designed a waste economy!

Growthism: sell more!

Why is this happening? Because most business models in our linear economy focus on growing revenue: by selling more products, making things cheaper – often by making them less repairable. In Resilience back in 2016, Erik Lindberg, described the modern ideology of ‘growthism’, challenging its perceived benefits. A

Another ‘sell more’ strategy is planned obsolescence: a few years ago, Apple was fined millions of dollars for slowing down older models of the iPhone, just to nudge us into buying the next model.

When we try to pay too little for things, it usually means exploiting labour, promoting slavery, creating more pollution of otherwise externalising the damage. Low prices often carry high costs. We in the West can’t afford the true costs of what we think we deserve. Less is more.

Douglas Rushkoff, author of Team Human and Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus

(@rushkoff on Twitter, 3 Feb 2020)

Author and thinker Douglas Rushkoff uncovers the problems behind those strategies: when we make things cheaper, somebody or something gets exploited. We need a different mindset – that less is more. It’s about caring for things – quality, not quantity.

It seems clear – the only way we will shrink our footprint is to reduce production and consumption. This means designing a system fit for the future: a system that works within the limits of resources, ecosystems, and planetary boundaries. We need better ways to regenerate what we need, not exhaust it.

False solutions

We’ve touched on the wicked problems and their root causes, so now let’s look at some of the false solutions that are coming into play.

For Earth Day this year, US campaign group Truth in Advertising (TINA) published a list of allegations related to sustainability claims for well-known brands. These ‘greenwashing’ claims included ‘100% recyclable’, ‘low-carbon’ and ‘sustainable’.

I’m also noticing increasing PR content, from companies promoting their circular and sustainable innovations. Let’s look at some examples, cross-checking their potential for unforeseen consequences.

Sweet-talkin’…

Funding is flooding into research for a variety of ‘new generation’ materials: innovations to replace virgin technical materials (fossil-based plastics, or metals and minerals). Often, this means switching to biological materials – food, fibres, and timber – but that’s not always better. Sometimes, these can be from abundant natural sources, such as algae, but mostly, they are from land-based crops.

Dutch biochemicals company Avantium has developed a 100% plant-based plastic for bottles and films, made from sugars, and said to be 100% recyclable. Avantium is teaming up with brands like Carlsberg, and says it sources ‘sustainably grown plants’ – but what does that mean?

Ecologists worry that these materials will encourage more deforestation and industrialised agriculture – they remind us that land and water are finite resources, and already under pressure. Rather than converting even more land to agriculture, we need to reforest and rewild our land to support biodiversity and capture carbon. Growing crops to make packaging and other short-life products just places more pressure on land, water and nature.

Using agricultural waste is a better choice. I noticed lots of posts celebrating the innovative materials in the UGG Fluff Sugar sandal. Footwear News tells us: “They feature a foam outsole made of renewable sugarcane, called SugarSole, while the soft, fluffy uppers are produced using plant-based Tencel Lyocell, which transforms wood pulp into fibres.”

However, even when we use agricultural waste to create new materials, there may be unintended or undesirable consequences. For example, if we’re buying waste sugar cane from the sugar supply chain, we’re improving the profits of sugar growing businesses.

We all know that sugar is not necessary for our wellbeing – in fact, it’s highly addictive and harmful to human health. The question is, do we really want to improve the profitability of the sugar industry? Both sugar cane and sugar beet have their critics. Feedback, a campaign group working to regenerate nature by transforming our food system, published The Dark Truth about Sugar Beet, uncovering the hidden damage growing sugar beet is doing to our soil.

‘Bio’ isn’t necessarily better

Bio can be a very misleading term. Legally, bio-based plastics might be made from organic matter – from plants and animals. But often it’s mixed with fossil-based chemicals.

Bioplastics are not necessarily biodegradable – and even if those plastics are biodegradable, there might not be a suitable treatment system nearby. Industrial composting facilities are few and far between, and even if the materials are biodegradable in the soil, that still creates microplastics and plastic pollution.

To find out more, check out these infographics from Zero Waste Europe and Rethink Plastics

Designing waste out of the system

Another recent material innovation is Nike Flyleather. Nike aims to design waste out of the leather manufacturing process, by using up those leather off cuts from shoes to make a new material. Reducing manufacturing waste (and its associated cost) is a good thing. However, this example combines the natural leather with a synthetic material, creating a new fabric that blends biological and technical materials. The downside is fabric that’s more difficult to recycle back into a new material at the end of its lifetime.

Recyclable?

Another ‘sustainability improvement’ is for companies to say they’ve increased the proportion of recyclable content in their products. Sounds good… but it’s not that simple! The product may be sold in regions with no suitable recycling facilities, meaning the company has passed the problem onto the local community. Recyclable in theory doesn’t guarantee a practical and cost-effective way to get that material back into the system.

Recycling technologies are also being questioned. In its ‘False Solutions’ fact sheet, Beyond Plastics warns that: ‘As the global plastic pollution crisis continues to grow, so does industry hype promoting false solutions including so-called “waste-to-energy” incineration, pyrolysis, “chemical recycling”, and other techno “fixes” that will enable the plastics industry to continue producing more and more plastic, worsening the crisis.

Sustainable materials

What about ‘sustainable materials’? You’ve probably noticed that many companies are talking about their sustainable materials, but there’s no legal definition of sustainability. Instead, every company can decide on its own criteria. In particular, the packaging and the fashion sectors seem to be promoting their ‘sustainable materials’. In this recent example, fashion brand H&M says its definition of sustainable means ‘at least 50% of a product’.

In the UK, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has published guidelines, warning of legal action if companies are found to be ‘greenwashing’. The CMA’s 2020 investigation (working alongside other global authorities) found that 40% of green claims made online could be misleading – suggesting that thousands of businesses could be breaking the law and risking their reputation.

This summer, sustainability media group edie reported that a study of the websites of 12 of the biggest British and European fashion brands, including Asos, H&M and Zara, has found that 60% of the environmental claims could be classed as “unsubstantiated” and “misleading”.

The ‘Synthetics Anonymous’ report by the Changing Markets Foundation, assessed brands across the spheres of fast fashion, luxury fashion and online retailing based on their sustainability claims. The brands also included Boohoo, Gucci, Louis Vuitton, Marks & Spencer (M&S), Uniqlo, and Walmart.

Across all 12 brands, 39% of products assessed came with sustainability-related claims such as “recycled”, “eco”, “low-impact” or simply “sustainable”. The Foundation assessed whether these claims stood up against the UK Competition and Markets Authority’s (CMA) new guidelines on avoiding greenwashing, finding that 59% did not.

What about the packaging sector? Talking Trash, a major report by Changing Markets, investigates industry tactics ‘in the face of an unprecedented plastic pollution crisis’ amid growing pressure to address it.

Spanning 15 countries and regions across five continents, the report reveals ‘how – behind the veil of nice-sounding initiatives and commitments – the industry has obstructed and undermined proven legislative solutions for decades.’

From false solutions to ‘rebound’…

So that’s a roundup of some of the false solutions undermining circular pathways to a sustainable, fair and prosperous world. In part two, I’ll be unpicking the tricky topic of ‘rebound’ [spoiler alert – it’s nothing to do with relationships!].

Stay in touch so you don’t miss out on our articles, podcasts and other useful stuff we share. If you’d like to read more on Greenwash, here’s a an article I wrote earlier this year: Is greenwashing undermining YOUR sustainability work?

Catherine Weetman advises businesses, gives workshops & talks, and writes about the circular economy. Her award-winning Circular Economy Handbook explains the concept and practicalities, in plain English. It includes lots of real examples and tips on getting started.

To find out more about the circular economy, why not listen to Episode 1 of the Circular Economy Podcast, read our guide: What is the Circular Economy, or stay in touch to get the latest episode and insights, straight to your inbox…